Encouraged to inform on each other

Imagine growing up in a society where deception, oppression, and aggression invade your everyday life. That is the existence of Joseph Nagyvary, a young boy with big dreams and yearning for a violin in post–World War II Hungary.

Joseph recollects a childhood growing up with a devout Catholic father and a rebellious Communist brother. In an atmosphere where everyone is encouraged to inform on each other, he doesn’t know whom he can trust. When Joseph attends the University of Budapest, he becomes involved in the 1956 uprising against the Soviet army. Violence and Violins details the horrors and panic that follow.

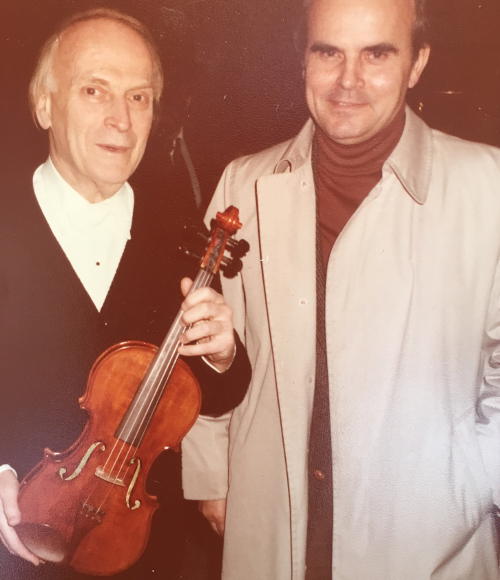

Joseph Nagyvary fled communism and eventually immigrated to the United States, where he taught biochemistry at Texas A&M University for thirty-eight years. Nagyvary’s work has been featured on news programs and PBS. He has been internationally awarded and recognized for his research on Stradivarius violins.

Coming of Age in post-World War II Hungary

Joseph Nagyvary’s father, János, was the only survivor of his division with Hungary’s 2nd Army. When he came back to his family after the horrors of World War II, his mission for God clashed with the atheistic Communist state in Hungary.

Growing up, young Joseph has two passions in life: science and music. He is particularly enamored of the Stradivarius violin. His fascination with the violin will lead to a lifelong pursuit, but his childhood gives him no opportunity to play any kind of musical instrument. Joseph chooses to pursue his other dream and enrolls as a chemistry major at the University of Budapest. He finds escape from the harsh reality of the communist terror by daydreaming of being the biblical Joseph, singing Wagner operas, and playing a Stradivarius.

In the only shooting war of the Cold War in 1956, Joseph’s life is forever changed. He will face enemy soldiers and have to choose whether or not to destroy them. Join him in this harrowing story about faith and peace amid paranoia and violence.

Author Biography

Joseph Nagyvary is professor emeritus of biochemistry at Texas A&M University. He studied chemistry in his native Hungary at the University of Budapest and was a participant in the 1956 student uprising.

Nagyvary later escaped to Austria and ended up in Switzerland. He earned his doctorate at the University of Zurich and completed his postdoctoral work at Cambridge University. After Cambridge, Nagyvary immigrated to the United States in 1964. He taught biochemistry at Texas A&M University from 1968 to 2003. He won a prize from the Swiss National Foundation in 1962, a career development award from US Public Health in 1967, and the Gold Medal of the Japanese Society for Industrial Physics in 2005.

Nagyvary has received international recognition for his research into the Stradivarius violin, inspired by a childhood passion for classical music. Nagyvary lives in Jonestown, Texas, with his wife, Mary Ann. He has four children.

Violence and Violins - Excerpts

1. Prologue

For years, I managed to avoid any conscious reflection on the horrifying days of my escape through the Iron Curtain after the fall of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising. While flying to Austria in the year 2000, something happened at a time I least expected that triggered my memory, a stream of old images that suddenly emerged out of nowhere. Unlike childhood hardships that often turn to fond memories by layers of time, like blemishes of antique violins blurred to a pleasing patina, these memories were covered by the dark soot of a subconscious shame which I could no longer avoid confronting.

Late in the afternoon on May 29, 2000 after twenty hours of air travel and a sleepless night, I was going through cycles of fatigue, apathy, vitality, and lethargy. Sitting in a window seat like a zombie, I hardly registered the changes of the land 20,000 feet below until the sun's reflection from a large body of water hit my eyes, and the captain announced that we were flying above Lake Neusiedler, which straddles the Austrian-Hungarian border. The captain's words set the gears of my mind in motion. First I recalled from my sixth grade geography class that this lake is surrounded by extended swamplands, which are transected by canals. Indeed, from the south end of the lake there was a straight shiny light of reflection indicating a channel running to the east. I beheld this view for awhile still in a state of idle torpor, then suddenly my cerebral synapses began to fire. Within seconds I became agitated enough to exclaim loudly, "This is the canal where I crossed the Iron Curtain when I escaped from Hungary in 1956!" I had been back to Hungary before on direct flights to Budapest, but that route was far from my exit point as a refugee. During my escape, I had no map of the area, and went around on a desultory path, often going in circles, searching for the border canal among several canals. This was the first time I had gotten a clear bird’s-eye view of the main canal representing the Austrian-Hungarian border.

This announcement caught the attention of my daughter Katie, who sat in front of me, and she repeated it to her boyfriend Sam. Soon, word got around to all members of our large travel group, and it served as a good wake-up call. Our airplane that was circling in a holding pattern for a long time finally received permission to land in Vienna's Schwechat airport. I had to forget about the swamp and the canal and begin concentrating on my duties as a chaperone of the students of A&M Consolidated High School of College Station, Texas. I was one of fourteen adults chaperoning my daughter's high school orchestra of ninety students on a tour of Central Europe, and we were beginning our initial descent into Austria.

Violence and Violins - Excerpts

10. Solace of Music

"Get yourself a violin, and go to see Mr. Schlosser, the violin teacher. He is the most accomplished violinist in town. You can see him in action at a Beethoven recital this weekend."

Like most recitals in the music school, it was free to the public, and I was there early to secure a seat in the first row. Mr. Emil Schlosser, a stogy little man with imperious demeanor, was well past his prime, but he enjoyed a good reputation as a pillar of chamber music in Kaposvár for at least 30 years. He managed to conjure up his sweetest tone in his opening piece, the "Romance in F" by Beethoven, which instantly became my favorite melody that stuck forever in my mind. Then he proceeded to enter a musical minefield called the "Kreutzer Sonata," which proved to be too treacherous for him. As hard as he tried to assert his control by jerking his head and breathing in and out gravely, much of the effort yielded a lot of scratchy sound. Still, he could have been a great teacher, and I was looking forward to meeting him.

Back at home I broke the great news to my usually depressed mother that I wanted to study the violin and become a virtuoso. She gave me a long pensive look, which gave way to a dismissive sigh.

"I thought you’d have come to realize by now the conditions we are in. I have to worry about what you eat tomorrow. Why do you think we eat a simple roux with only caraway seeds every other day? Why don’t we buy any clothing and shoes? We certainly have no money for luxuries like violin lessons. It's almost insignificant that we no longer have a violin. This topic is closed. Don’t mention it again."

Her declaration was like a cold shower to me. No violin! What happened to the violin Father used to play, the source of the sweet sound I heard so often as a child? I asked my brother if he knew about the fate of our family violin, but he offered only guesses. It could have been taken by any of the soldiers who were stationed at our house from Germany, Italy, Bulgaria, or Russia. There was no way to retrieve it, if it survived the war at all. Laci assumed that Mother could have traded the violin for food.

28. Bibi, the girlfriend I almost had

Bibi was a sight to behold after seeing her previously in her overcoat. In her pastel colored, form-fitting knitted blouse, maybe cashmere, she looked as well-endowed as Gina Lollobrigida, the much admired star of the Italian cinema. Our seats were on the extreme left side in rows 3 and 4. I had kept the two best seats in row 3 for Bibi and me with the others sitting right behind us. There was a bulky Dorian column to the left of Bibi that completely blocked the view of Bandi behind her.

The performance itself was outstanding, as anticipated given a distinguished cast, featuring the A-team of the soloists, all salaried regulars. The great star of the evening was the basso Mihály Székely, who had only a few years earlier been singing with the New York Metropolitan Opera, and according to his American critics, could arguably have been the best basso profondo voice in the entire world.

It took only a few glances to notice that Bibi was also in musical heaven, sharing fully my enjoyment of the great arias and duets even without seeing the protagonists. The only way to see more of the stage and the ongoing action was to hold onto the column and lean as far forward as possible. We took turns doing that whenever there was a change of scenes to have at least an idea where the principals happened to be while they were singing their hearts out passionately and earning well-deserved ovations. Sitting by the column, Bibi had the lion’s share of the acrobatic viewing.

At the appropriate moment, I whispered to Bibi that my favorite highlight would happen soon, the solo act of the court lady Eboli, the king’s lover, who would sing the greatest mezzo-soprano aria Verdi ever wrote, “O Don Fatale." In her aria, in the throes of contradicting emotions, she curses her beauty and sex appeal that drew all men in and also begs the forgiveness of the queen for betraying her trust. I had to see how this top act would be negotiated, so I climbed back to the narrow walkway and moved to the center of the floor space near the entrance. Eboli also moved to the front center of the stage and began singing the lyrical passage of “O mia regina” in a deep resonant chest tone. I looked to the left to see how Bibi was doing, and I saw her in a precarious position, holding onto the column with one hand and leaning out at a sharp angle with Bandi holding her other hand for support. From my point of view, it looked like a dangerous position because she could lose her grip, tumble forward, and who knows, even end up on the orchestra floor. I was not the only one noticing this distraction. More heads were turned to the left to see Bibi’s act than the stage. Bibi was oblivious to all this; she was raptly watching the scene. I wish I could have made a photograph of her in this position, which would have inspired artists of the caliber of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Her silhouette had a delicious design. With her arms pulled back, her already generous bust-line received an added emphasis, and those who were fortunate to scrutinize it had witnessed something close to perfection. The combination of risqué behavior and allure in its nonchalant exhibition was irresistible to all the eyes on the third floor who got their money’s worth that evening. As long as I live, I will never forget coupling Eboli and Bibi together, the two femme fatales in concerted action.

44. Love or kill your enemies: October 27, Saturday

We waited ready for an ambush less than half an hour when shouts alerted us that an enemy vehicle was about to enter our area from the direction of the National Theater from our right. It was an armored personnel carrier, or possibly a reconnaissance vehicle. It had six wheels with rubber tires and a partially open top with a heavy machine gun in the front. The men at Szentkirályi Street corner were the first ones to open fire with their small arms. The Russian driver elected to speed up while the gunner also began to fire. In the midst of the loud rattle, I heard Laci shouting.

"Aim at the wheels only!" He hollered with all his might. Upon his command, all the men on the corner started firing at the Russians' tires as the vehicle was approaching Puskin Street. The rapid banging of their guns resounded on the high stone walls that flanked the street as smoke filled the air. The moment was intoxicating, and I could not resist joining the action. I readied my submachine gun, and began firing as soon as the troop carrier appeared in my view passing the intersection. My ears were ringing and hurting. My aim was less than perfect as it veered from the low front wheel upward to the top of the armor, but I think I did my share of damage to the front tire.

In a matter of seconds, the front right tire was blown off in pieces, and the carrier began to veer to the right as it passed through my limited viewing angle from Puskin Street. I ran forward to the corner to see the outcome. The driver lost control of the craft which ran up onto the pedestrian pavement and came to a halt by slamming against the wall of the apartment building straight across from the dormitory.